what are the different job design approaches to motivation

half-dozen.ii Motivating Employees Through Chore Design

Learning Objectives

- Acquire about the history of job pattern approaches.

- Consider alternatives to job specialization.

- Identify chore characteristics that increment motivating potential.

- Acquire how to empower employees.

Importance of Chore Design

Many of usa presume the most of import motivator at work is pay. Yet studies point to a different factor as the major influence over worker motivation—job design. How a job is designed has a major bear on on employee motivation, job satisfaction, delivery to an organization, absence, and turnover.

The question of how to properly design jobs so that employees are more productive and more satisfied has received attention from managers and researchers since the beginning of the 20th century. Nosotros volition review major approaches to task design starting from its early on history.

Scientific Direction and Job Specialization

Perhaps the earliest endeavor to design jobs came during the era of scientific management. Scientific management is a philosophy based on the ideas of Frederick Taylor as presented in his 1911 book, Principles of Scientific Direction. Taylor's book was among the almost influential books of the 20th century; the ideas presented had a major influence over how work was organized in the following years. Taylor was a mechanical engineer in the manufacturing manufacture. He saw piece of work being done haphazardly, with only workers in charge. He saw the inefficiencies inherent in employees' product methods and argued that a manager's job was to advisedly plan the work to exist performed by employees. He also believed that scientific methods could be used to increase productivity. As an example, Taylor constitute that instead of allowing workers to use their ain shovels, every bit was the custom at the time, providing specially designed shovels increased productivity. Further, past providing training and specific instructions, he was able to dramatically reduce the number of laborers required to handle each job (Taylor, 1911; Wilson, 1999).

Figure 6.ii

This Ford console assembly line in Berlin, Frg, is an example of specialization. Each person on the line has a different job.

Scientific direction proposed a number of ideas that have been influential in task design in the following years. An important idea was to minimize waste by identifying the almost efficient method to perform the job. Using time–motion studies, management could determine how much time each task would require and program the tasks and then that the job could be performed as efficiently as possible. Therefore, standardized chore performance methods were an important chemical element of scientific management techniques. Each job would be carefully planned in advance, and employees would exist paid to perform the tasks in the way specified past management.

Furthermore, job specialization was 1 of the major advances of this approach. Job specialization entails breaking down jobs into their simplest components and assigning them to employees and so that each person would perform a select number of tasks in a repetitive manner. There are a number of advantages to job specialization. Breaking tasks into uncomplicated components and making them repetitive reduces the skill requirements of the jobs and decreases the effort and toll of staffing. Grooming times for simple, repetitive jobs tend to be shorter every bit well. On the other hand, from a motivational perspective, these jobs are boring and repetitive and therefore associated with negative outcomes such as absenteeism (Campion & Thayer, 1987). Besides, job specialization is ineffective in chop-chop changing environments where employees may demand to alter their approach according to the demands of the state of affairs (Wilson, 1999).

Today, Taylorism has a bad reputation, and it is often referred to as the "nighttime ages" of management when employees' social motives were ignored. Yet, it is important to recognize the fundamental change in management mentality brought virtually past Taylor's ideas. For the first time, managers realized their role in influencing the output levels of employees. The concept of scientific management has had a lasting touch on how work is organized. Taylor'south piece of work paved the fashion to automation and standardization that is near universal in today'southward workplace. Associates lines where each worker performs simple tasks in a repetitive manner are a direct issue of job specialization efforts. Job specialization eventually plant its way to the service industry every bit well. One of the biggest innovations of the famous McDonald brothers' starting time fast-food restaurant was the application of scientific direction principles to their operations. They divided up the tasks so that one person took the orders while someone else made the burgers, another person applied the condiments, and yet some other wrapped them. With this level of efficiency, customers mostly received their order within 1 minute (Spake, 2001; Business heroes, 2005).

Rotation, Chore Enlargement, and Enrichment

One of the early alternatives to chore specialization was job rotation. Job rotation involves moving employees from chore to job at regular intervals. When employees periodically movement to different jobs, the monotonous aspects of job specialization can be relieved. For example, Maids International Inc., a company that provides cleaning services to households and businesses, utilizes job rotation and then that maids cleaning the kitchen in one house would clean the chamber in a different one (Denton, 1994). Using this technique, amid others, the company is able to reduce its turnover level. In a supermarket study, cashiers were rotated to piece of work in different departments. Every bit a result of the rotation, employees' stress levels were reduced, every bit measured past their blood pressure level. Moreover, they experienced less hurting in their neck and shoulders (Rissen et al., 2002).

Job rotation has a number of advantages for organizations. It is an effective style for employees to acquire new skills and in turn for organizations to increase the overall skill level of their employees (Campion, Cheraskin, & Stevens, 1994). When workers move to different positions, they are cross-trained to perform dissimilar tasks, thereby increasing the flexibility of managers to assign employees to different parts of the system when needed. In addition, task rotation is a manner to transfer knowledge between departments (Kane, Argote, & Levine, 2005). Rotation may also have the do good of reducing employee boredom, depending on the nature of the jobs the employee is performing at a given time. From the employee standpoint, rotation is a benefit, considering they acquire new skills that keep them marketable in the long run.

Is rotation used only at lower levels of an system? Anecdotal evidence suggests that companies successfully rotate high-level employees to railroad train managers and increment innovation in the company. For example, Nokia uses rotation at all levels, such as assigning lawyers to deed as state managers or moving network engineers to handset design. This approach is idea to bring a fresh perspective to old bug (Wylie, 2003). Wipro Ltd., India'southward it giant that employs well-nigh eighty,000 workers, uses a 3-year plan to groom time to come leaders of the company by rotating them through different jobs (Ramamurti, 2001).

Chore enlargement refers to expanding the tasks performed past employees to add more than multifariousness. By giving employees several different tasks to exist performed, equally opposed to limiting their activities to a minor number of tasks, organizations hope to reduce boredom and monotony as well as apply human being resources more finer. Task enlargement may have similar benefits to job rotation, considering it may likewise involve teaching employees multiple tasks. Research indicates that when jobs are enlarged, employees view themselves every bit being capable of performing a broader set of tasks (Parker, 1998). There is some evidence that job enlargement is beneficial, because information technology is positively related to employee satisfaction and higher quality client services, and information technology increases the chances of catching mistakes (Campion & McClelland, 1991). At the aforementioned time, the furnishings of job enlargement may depend on the type of enlargement. For case, chore enlargement consisting of adding tasks that are very uncomplicated in nature had negative consequences on employee satisfaction with the job and resulted in fewer errors existence caught. Alternatively, giving employees more tasks that require them to be knowledgeable in different areas seemed to have more positive effects (Campion & McClelland, 1993).

Chore enrichment is a job redesign technique that allows workers more than control over how they perform their ain tasks. This approach allows employees to take on more responsibility. Every bit an alternative to chore specialization, companies using task enrichment may experience positive outcomes, such as reduced turnover, increased productivity, and reduced absences (McEvoy & Cascio, 1985; Locke, Sirota, & Wolfson, 1976). This may exist considering employees who have the potency and responsibility over their work can be more than efficient, eliminate unnecessary tasks, take shortcuts, and increment their overall performance. At the same fourth dimension, there is evidence that task enrichment may sometimes crusade dissatisfaction among certain employees (Locke, Sirota, & Wolfson, 1976). The reason may be that employees who are given additional autonomy and responsibility may expect greater levels of pay or other types of bounty, and if this expectation is not met they may experience frustrated. One more than matter to think is that job enrichment is non suitable for everyone (Cherrington & Lynn, 1980; Hulin & Claret, 1968). Not all employees desire to have command over how they work, and if they do not have this want, they may become frustrated with an enriched job.

Task Characteristics Model

The job characteristics model is 1 of the about influential attempts to pattern jobs with increased motivational backdrop (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). Proposed past Hackman and Oldham, the model describes five core task dimensions leading to 3 critical psychological states, resulting in work-related outcomes.

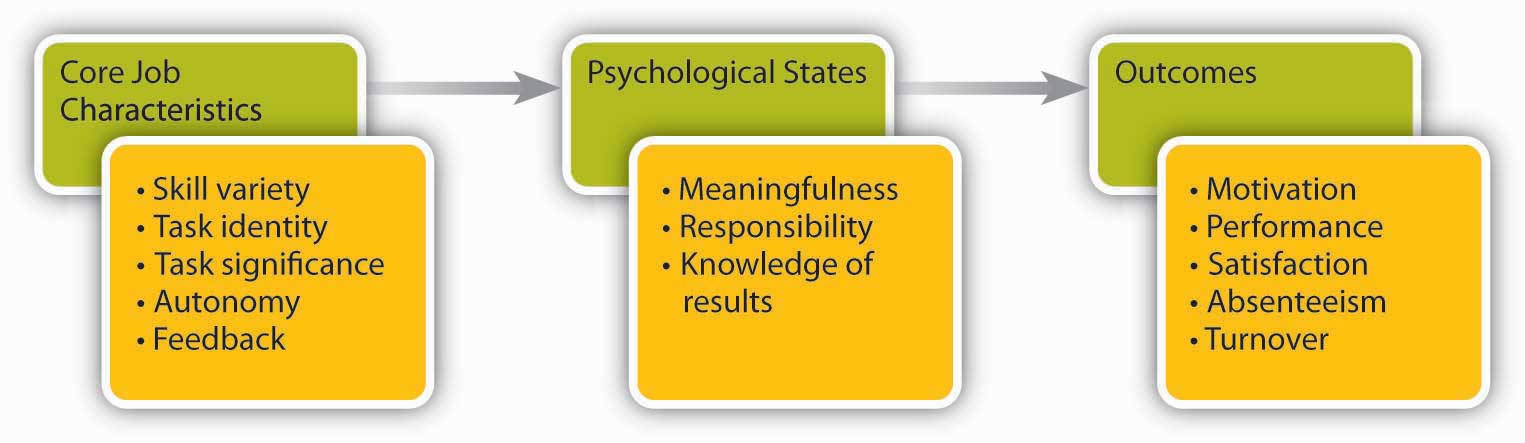

Effigy 6.3

The Chore Characteristics Model has five core job dimensions.

Source: Adapted from Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, 1000. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 159–170.

Skill multifariousness refers to the extent to which the job requires a person to utilize multiple high-level skills. A car wash employee whose chore consists of directing customers into the automated auto launder demonstrates depression levels of skill variety, whereas a auto launder employee who acts as a cashier, maintains carwash equipment, and manages the inventory of chemicals demonstrates high skill diverseness.

Job identity refers to the caste to which a person is in charge of completing an identifiable work from start to cease. A Web designer who designs parts of a Web site will take low task identity, because the piece of work blends in with other Spider web designers' work; in the end it will be difficult for whatever one person to claim responsibility for the final output. The Web master who designs an entire Web site volition accept high task identity.

Job significance refers to whether a person's job essentially affects other people's work, health, or well-being. A janitor who cleans the floors at an office building may observe the job low in significance, thinking it is not a very of import job. Nonetheless, janitors cleaning the floors at a infirmary may see their role equally essential in helping patients get amend. When they feel that their tasks are significant, employees tend to feel that they are making an impact on their environment, and their feelings of self-worth are additional (Grant, 2008).

Autonomy is the degree to which a person has the freedom to decide how to perform his or her tasks. As an case, an instructor who is required to follow a predetermined textbook, covering a given list of topics using a specified list of classroom activities, has depression autonomy. On the other hand, an instructor who is free to choose the textbook, design the course content, and use any relevant materials when delivering lectures has higher levels of autonomy. Autonomy increases motivation at work, only it also has other benefits. Giving employees autonomy at work is a key to individual as well as company success, because autonomous employees are free to choose how to do their jobs and therefore can exist more constructive. They are too less likely to prefer a "this is not my job" approach to their piece of work environment and instead exist proactive (practice what needs to be done without waiting to be told what to do) and creative (Morgeson, Delaney-Klinger, & Hemingway, 2005; Parker, Wall, & Jackson, 1997; Parker, Williams, & Turner, 2006; Zhou, 1998). The outcome of this resourcefulness tin can be higher visitor operation. For example, a Cornell University study shows that small businesses that gave employees autonomy grew four times more than those that did non (Davermann, 2006). Giving employees autonomy is also a great fashion to train them on the chore. For example, Gucci's CEO Robert Polet points to the level of autonomy he was given while working at Unilever PLC equally a central to his development of leadership talents (Gumbel, 2008). Autonomy tin arise from workplace features, such equally telecommuting, visitor construction, organizational climate, and leadership style (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007; Garnier, 1982; Lyon & Ivancevich, 1974; Parker, 2003).

Feedback refers to the degree to which people learn how effective they are being at work. Feedback at work may come up from other people, such as supervisors, peers, subordinates, and customers, or it may come from the chore itself. A salesperson who gives presentations to potential clients merely is not informed of the clients' decisions, has depression feedback at work. If this person receives notification that a sale was fabricated based on the presentation, feedback will exist loftier.

The relationship between feedback and task performance is more controversial. In other words, the mere presence of feedback is not sufficient for employees to experience motivated to perform better. In fact, a review of this literature shows that in almost ane-third of the cases, feedback was detrimental to performance (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). In add-on to whether feedback is present, the sign of feedback (positive or negative), whether the person is fix to receive the feedback, and the manner in which feedback was given will all make up one's mind whether employees feel motivated or demotivated as a outcome of feedback.

According to the task characteristics model, the presence of these five cadre job dimensions leads employees to experience 3 psychological states: They view their work equally meaningful, they feel responsible for the outcomes, and they acquire knowledge of results. These three psychological states in plough are related to positive outcomes such as overall job satisfaction, internal motivation, higher performance, and lower absence and turnover (Brass, 1985; Humphrey, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, 2007; Johns, Xie, & Fang, 1992; Renn & Vandenberg, 1995). Research shows that out of these three psychological states, experienced meaningfulness is the most of import for employee attitudes and behaviors, and it is the key mechanism through which the five cadre job dimensions operate.

Are all five job characteristics equally valuable for employees? Hackman and Oldham's model proposes that the five characteristics volition not have uniform furnishings. Instead, they proposed the following formula to summate the motivating potential of a given chore (Hackman & Oldham, 1975):

Equation 6.1

MPS = ((Skill Variety + Task Identity + Task Significance) ÷ 3) × Autonomy × Feedback

According to this formula, autonomy and feedback are the more important elements in deciding motivating potential compared to skill diversity, task identity, or task significance. Moreover, note how the job characteristics interact with each other in this model. If someone'southward chore is completely defective in autonomy (or feedback), regardless of levels of variety, identity, and significance, the motivating potential score will be very depression.

Note that the five job characteristics are not objective features of a job. Two employees working in the aforementioned job may have very unlike perceptions regarding how much skill diverseness, chore identity, task significance, autonomy, or feedback the job affords. In other words, motivating potential is in the middle of the beholder. This is both adept and bad news. The bad news is that fifty-fifty though a manager may design a job that is supposed to motivate employees, some employees may not observe the task to be motivational. The skilful news is that sometimes it is possible to increase employee motivation by helping employees change their perspective about the job. For case, employees laying bricks at a structure site may feel their jobs are depression in significance, just by pointing out that they are building a dwelling house for others, their perceptions most their job may be changed.

Do all employees expect to have a job that has a loftier motivating potential? Research has shown that the want for the five core job characteristics is not universal. 1 factor that affects how much of these characteristics people want or need is growth demand strength. Growth demand strength describes the caste to which a person has college order needs, such equally self-esteem and cocky-appearing. When an employee's expectation from his job includes such higher order needs, employees will have high-growth need strength, whereas those who await their job to pay the bills and satisfy more basic needs will have low-growth demand forcefulness. Not surprisingly, research shows that those with high-growth need strength respond more favorably to jobs with a high motivating potential (Arnold & House, 1980; Hackman & Lawler, 1971; Hackman & Oldham, 1975; Oldham, Hackman, & Pearce, 1976). Information technology also seems that an employee's career stage influences how important the v dimensions are. For example, when employees are new to an organisation, chore significance is a positive influence over job satisfaction, but autonomy may be a negative influence (Katz, 1978).

OB Toolbox: Increase the Feedback You Receive: Seek Information technology!

- If yous are not receiving enough feedback on the job, it is better to seek it instead of trying to guess how you are doing. Consider seeking regular feedback from your boss. This also has the added benefit of signaling to the manager that you care about your operation and want to exist successful.

- Be genuine in your desire to learn. When seeking feedback, your aim should exist improving yourself as opposed to creating the impression that you lot are a motivated employee. If your managing director thinks that you are managing impressions rather than genuinely trying to improve your performance, seeking feedback may hurt you.

- Develop a good relationship with your manager. This has the benefit of giving you more feedback in the first place. It also has the upside of making it easier to enquire straight questions virtually your own performance.

- Consider finding trustworthy peers who tin can share information with you regarding your performance. Your manager is non the only helpful source of feedback.

- Be gracious when you receive feedback. If you automatically get on the defensive the offset time yous receive negative feedback, there may not be a next fourth dimension. Remember, even if receiving feedback, positive or negative, feels uncomfortable, it is a gift. You can ameliorate your functioning using feedback, and people giving negative feedback probably feel they are risking your good volition by being honest. Be thankful and appreciative when you receive any feedback and do not endeavour to convince the person that information technology is inaccurate (unless at that place are factual mistakes).

Sources: Adapted from ideas in Jackman, J. M., & Strober, M. H. (2003, April). Fear of feedback. Harvard Concern Review, 81(4), 101–107; Fly, L., Xu, H., Snape, E. (2007). Feedback-seeking behavior and leader-member exchange: Practise supervisor-attributed motives thing? Academy of Management Journal, 50, 348–363; Lee, H. E., Park, H. S., Lee, T. S., & Lee, D. Due west. (2007). Relationships between LMX and subordinates' feedback-seeking behaviors. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 35, 659–674.

Empowerment

1 of the contemporary approaches to motivating employees through job design is empowerment. The concept of empowerment extends the thought of autonomy. Empowerment may be divers as the removal of conditions that make a person powerless (Conger & Kanugo, 1988). The idea behind empowerment is that employees have the ability to make decisions and perform their jobs effectively if management removes certain barriers. Thus, instead of dictating roles, companies should create an surroundings where employees thrive, feel motivated, and have discretion to make decisions about the content and context of their jobs. Employees who feel empowered believe that their piece of work is meaningful. They tend to feel that they are capable of performing their jobs effectively, accept the ability to influence how the visitor operates, and can perform their jobs in whatsoever way they encounter fit, without close supervision and other interference. These liberties enable employees to feel powerful (Spreitzer, 1995; Thomas & Velthouse, 1990). In cases of very high levels of empowerment, employees decide what tasks to perform and how to perform them, in a sense managing themselves.

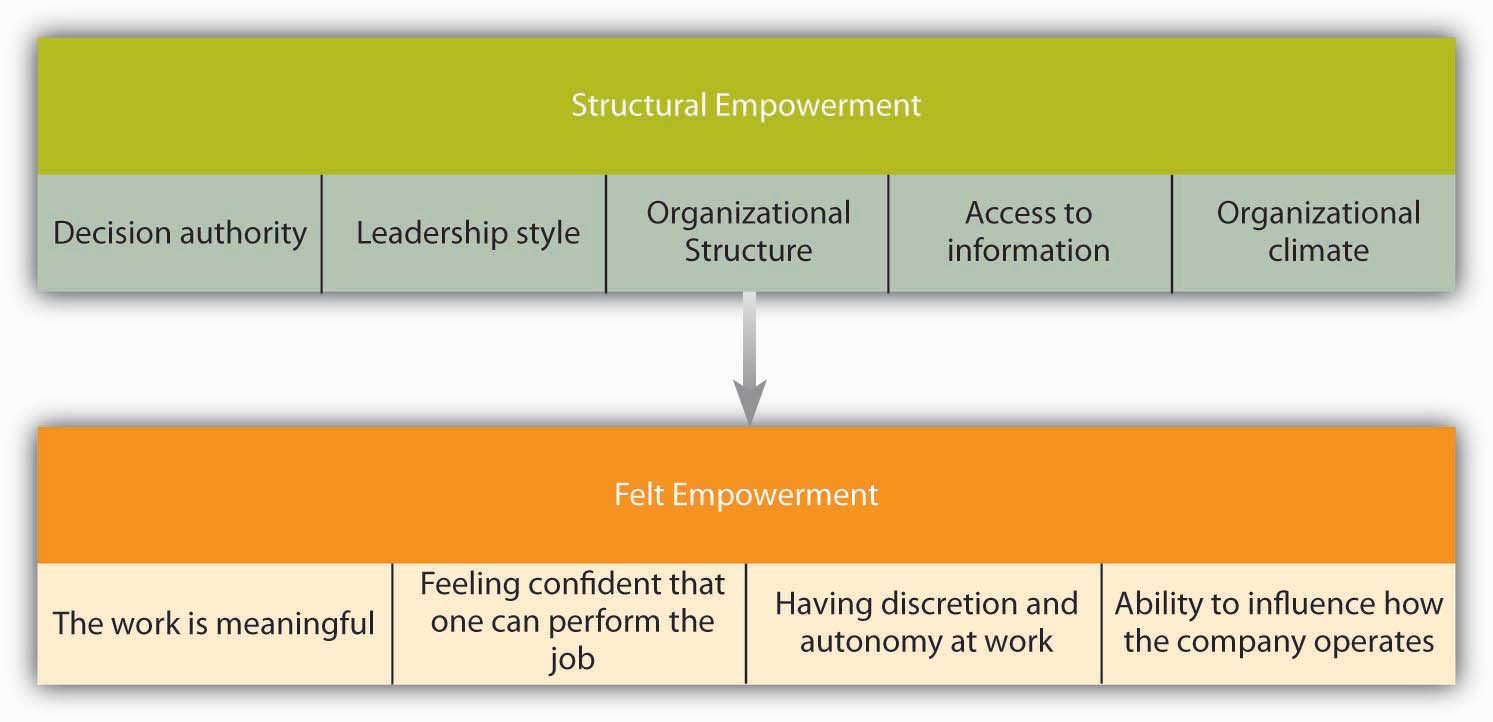

Research has distinguished between structural elements of empowerment and felt empowerment. Structural empowerment refers to the aspects of the work environment that give employees discretion, autonomy, and the power to exercise their jobs effectively. The idea is that the presence of certain structural factors helps empower people, but in the end empowerment is a perception. The post-obit effigy demonstrates the relationship between structural and felt empowerment. For case, at Harley-Davidson Motor Company, employees have the authority to end the production line if they see a blemish on the product (Lustgarten, 2004). Leadership style is another influence over experienced empowerment (Kark, Shamir, & Chen, 2003). If the manager is controlling, micromanaging, and snobby, chances are that empowerment will not be possible. A visitor's structure has a role in determining empowerment too. Factories organized effectually teams, such every bit the Saturn found of General Motors Corporation, can however empower employees, despite the presence of a traditional hierarchy (Ford & Fottler, 1995). Admission to information is often mentioned as a cardinal factor in empowering employees. If employees are not given information to make an informed decision, empowerment attempts will fail. Therefore, the human relationship between access to information and empowerment is well established. Finally, empowering individual employees cannot occur in a bubble, but instead depends on creating a climate of empowerment throughout the entire organization (Seibert, Silver, & Randolph, 2004).

Effigy vi.4

The empowerment procedure starts with construction that leads to felt empowerment.

Source: Based on the ideas in Seibert, South. Due east., Silver, S. R., & Randolph, West. A. (2004). Taking empowerment to the side by side level: A multiple-level model of empowerment, functioning, and satisfaction. Academy of Direction Journal, 47, 332–349; Spreitzer, Chiliad. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Periodical, 38, 1442–1465; Spreitzer, G. Thousand. (1996). Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 483–504.

Empowerment of employees tends to be benign for organizations, considering it is related to outcomes such equally employee innovativeness, managerial effectiveness, employee delivery to the organization, customer satisfaction, job operation, and behaviors that benefit the visitor and other employees (Ahearne, Mathieu, & Rapp, 2005; Alge et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007; Liden, Wayne, & Sparrowe, 2000; Spreitzer, 1995). At the same time, empowerment may non necessarily exist suitable for all employees. Those individuals with low growth forcefulness or low accomplishment need may not benefit equally strongly from empowerment. Moreover, the idea of empowerment is not always easy to implement, because some managers may feel threatened when subordinates are empowered. If employees practice non feel fix for empowerment, they may also worry nearly the increased responsibility and accountability. Therefore, preparing employees for empowerment by carefully selecting and training them is of import to the success of empowerment interventions.

OB Toolbox: Tips for Empowering Employees

- Change the company structure so that employees take more power on their jobs. If jobs are strongly controlled by organizational procedures or if every little decision needs to be canonical by a superior, employees are unlikely to feel empowered. Give them discretion at work.

- Provide employees with access to information near things that touch their work. When employees accept the information they need to do their jobs well and understand company goals, priorities, and strategy, they are in a better position to experience empowered.

- Make certain that employees know how to perform their jobs. This involves selecting the correct people as well as investing in continued training and evolution.

- Do not have away employee power. If someone makes a decision, let it stand unless it threatens the unabridged company. If direction undoes decisions made by employees on a regular ground, employees will not believe in the sincerity of the empowerment initiative.

- Instill a climate of empowerment in which managers practise not routinely pace in and take over. Instead, believe in the power of employees to make the well-nigh accurate decisions, every bit long equally they are equipped with the relevant facts and resources.

Sources: Adapted from ideas in Forrester, R. (2000). Empowerment: Rejuvenating a potent idea. Academy of Direction Executive, 14, 67–79; Spreitzer, G. M. (1996). Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 483–504.

Fundamental Takeaway

Job specialization is the earliest approach to chore design, originally described by the work of Frederick Taylor. Job specialization is efficient but leads to boredom and monotony. Early alternatives to job specialization include job rotation, task enlargement, and job enrichment. Research shows that there are v task components that increase the motivating potential of a job: Skill variety, job identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback. Finally, empowerment is a contemporary way of motivating employees through chore design. These approaches increase worker motivation and take the potential to increase performance.

References

Ahearne, M., Mathieu, J., & Rapp, A. (2005). To empower or not to empower your sales forcefulness? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment beliefs on customer satisfaction and performance. Journal of Practical Psychology, ninety, 945–955.

Alge, B. J., Ballinger, Chiliad. A., Tangirala, South., & Oakley, J. L. (2006). Data privacy in organizations: Empowering creative and extrarole performance. Journal of Practical Psychology, 91, 221–232.

Arnold, H. J., & Firm, R. J. (1980). Methodological and substantive extensions to the job characteristics model of motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Operation, 25, 161–183.

Contumely, D. J. (1985). Technology and the structuring of jobs: Employee satisfaction, performance, and influence. Organizational Behavior and Man Decision Processes, 35, 216–240.

Business heroes: Ray Kroc. (2005, Winter). Business Strategy Review, 16, 47–48.

Campion, M. A., Cheraskin, L., & Stevens, M. J. (1994). Career-related antecedents and outcomes of job rotation. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1518–1542.

Campion, M. A., & McClelland, C. L. (1991). Interdisciplinary examination of the costs and benefits of enlarged jobs: A job design quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 186–198.

Campion, Thou. A., & McClelland, C. L. (1993). Follow-upwards and extension of the interdisciplinary costs and benefits of enlarged jobs. Journal of Practical Psychology, 78, 339–351.

Campion, M. A., & Thayer, P. West. (1987). Job design: Approaches, outcomes, and merchandise-offs. Organizational Dynamics, 15, 66–78.

Chen, G., Kirkman, B. L., Kanfer, R., Allen, D., & Rosen, B. (2007). A multilevel written report of leadership, empowerment, and performance in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 331–346.

Cherrington, D. J., & Lynn, Eastward. J. (1980). The desire for an enriched task as a moderator of the enrichment-satisfaction relationship. Organizational Beliefs and Human Performance, 25, 139–159.

Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. Due north. (1988). The empowerment procedure: Integrating theory and practise. Academy of Management Review, 13, 471–482.

Davermann, Thousand. (2006, July). HR = College revenues? FSB: Fortune Small-scale Business, 16, 80–81.

Denton, D. K. (1994). …I hate this job. Business concern Horizons, 37, 46–52.

Ford. R. C., & Fottler, M. D. (1995). Empowerment: A matter of caste. Academy of Management Executive, nine, 21–29.

Gajendran, R. South., & Harrison, D. A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown most telecommuting. Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and private consequences. Periodical of Applied Psychology, 92, 1524–1541.

Garnier, Yard. H. (1982). Context and decision making autonomy in the strange affiliates of U.S. multinational corporations. Academy of Management Journal, 25, 893–908.

Grant, A. M. (2008). The significance of task significance: Job performance effects, relational mechanisms, and boundary conditions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 108–124.

Gumbel, P. (2008). Galvanizing Gucci. Fortune, 157(one), 80–88.

Hackman, J. R., & Lawler, East. E. (1971). Employee reactions to task characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 55, 259–286.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, threescore, 159–170.

Hulin, C. L., & Claret, Grand. R. (1968). Job enlargement, private differences, and worker responses. Psychological Bulletin, 69, 41–55.

Humphrey, S. E., Nahrgang, J. D., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: A meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work pattern literature. Periodical of Applied Psychology, 92, 1332–1356.

Johns, G., Xie, J. L., & Fang, Y. (1992). Mediating and moderating effects in job design. Periodical of Management, 18, 657–676.

Kane, A. A., Argote, L., & Levine, J. Grand. (2005). Knowledge transfer between groups via personnel rotation: Effects of social identity and knowledge quality. Organizational Behavior and Human being Decision Processes, 96, 56–71.

Kark, R., Shamir, B., & Chen, G. (2003). The 2 faces of transformational leadership: Empowerment and dependency. Journal of Practical Psychology, 88, 246–255.

Katz, R. (1978). Job longevity every bit a situational factor in task satisfaction. Administrative Scientific discipline Quarterly, 23, 204–223.

Kluger, A. Northward., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The furnishings of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 254–284.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Sparrowe, R. T. (2000). An examination of the mediating function of psychological empowerment on the relations between the job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. Journal of Practical Psychology, 85, 407–416.

Locke, East. A., Sirota, D., & Wolfson, A. D. (1976). An experimental case study of the successes and failures of chore enrichment in a government agency. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61, 701–711.

Lustgarten, A. (2004). Harley-Davidson. Fortune, 149(i), 76.

Lyon, H. Fifty., & Ivancevich, J. Thousand. (1974). An exploratory investigation of organizational climate and task satisfaction in a hospital. Academy of Management Journal, 17, 635–648.

McEvoy, G. M., & Cascio, Westward. F. (1985). Strategies for reducing employee turnover. Journal of Practical Psychology, 70, 342–353.

Morgeson, F. P., Delaney-Klinger, G., & Hemingway, One thousand. A. (2005). The importance of chore autonomy, cerebral power, and job-related skill for predicting role breadth and chore performance. Periodical of Applied Psychology, 90, 399–406.

Oldham, G. R., Hackman, J. R., & Pearce, J. L. (1976). Atmospheric condition nether which employees respond positively to enriched piece of work. Journal of Practical Psychology, 61, 395–403.

Parker, S. One thousand. (1998). Enhancing role breadth self-efficacy: The roles of job enrichment and other organizational interventions. Journal of Practical Psychology, 83, 835–852.

Parker, S. G. (2003). Longitudinal furnishings of lean production on employee outcomes and the mediating role of piece of work characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 620–634.

Parker, Southward. Thousand., Wall, T. D., & Jackson, P. R. (1997). "That's not my job": Developing flexible employee work orientations. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 899–929.

Parker, Due south. K., Williams, H. M., & Turner, N. (2006). Modeling the antecedents of proactive beliefs at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 636–652.

Ramamurti, R. (2001). Wipro's chairman Azim Premji on building a world-class Indian company. Academy of Management Executive, xv, 13–19.

Renn, R. West., & Vandenberg, R. J. (1995), The critical psychological states: An underrepresented component in job characteristics model research. Journal of Management, 21, 279–303.

Rissen, D., Melin, B., Sandsjo, L., Dohns, I., & Lundberg, U. (2002). Psychophysiological stress reactions, trapezius muscle activity, and neck and shoulder hurting among female cashiers before and later introduction of job rotation. Piece of work & Stress, 16, 127–137.

Seibert, S. E., Silver, S. R., & Randolph, W. A. (2004). Taking empowerment to the next level: A multiple-level model of empowerment, performance, and satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 332–349.

Spake, A. (2001). How McNuggets changed the earth. U.S. News & World Written report, 130(three), 54.

Spreitzer, G. One thousand. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Direction Journal, 38, 1442–1465.

Taylor, F. W. (1911). Principles of scientific management. American Mag, 71, 570–581.

Thomas, K. W., & Velthouse, B. A. (1990). Cognitive elements of empowerment: An "interpretive" model of intrinsic job motivation. University of Management Review, 15, 666–681.

Wilson, F. Thousand. (1999). Rationalization and rationality 1: From the founding fathers to eugenics. Organizational Behaviour: A Critical Introduction. Oxford, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Oxford Academy Printing.

Wylie, I. (2003, May). Calling for a renewable future. Fast Company, 70, 46–48.

Zhou, J. (1998). Feedback valence, feedback style, task autonomy, and achievement orientation: Interactive effects on creative performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 261–276.

khullsomearesove46.blogspot.com

Source: https://opentext.wsu.edu/organizational-behavior/chapter/6-2-motivating-employees-through-job-design/

0 Response to "what are the different job design approaches to motivation"

Post a Comment